Aegean Pushbacks Lead to Drowning

Whistleblowers claims new tactic of being thrown overboard off Turkish coast

Greece claims that its “strong but fair” border policing in the Aegean saves lives. The government points to an 80 percent drop in sea arrivals as a sign of its success. In reality, the policy is based on a regime of detaining newly-arrived asylum seekers on the Aegean islands and forcing them onto life rafts with no engines, then setting them adrift towards Turkey. The practice has been extensively documented by Lighthouse Reports and our media partners in previous investigations.

In September, the bodies of Sidy Keita, from Ivory Coast, and Didier Martial Kouamou Nana, from Cameroon, washed up on the Turkish coast. Their deaths suggested that a new and potentially life-threatening tactic is being deployed. The two men had been alive and well on the Greek island of Samos just days before, according to multiple witnesses. One of those witnesses, Ibrahim, says that he was with Sidy and Didier when they were captured by Greek authorities on the island, made to board a speedboat and then thrown overboard off the coast of Turkey. Working with Der Spiegel, The Guardian and Mediapart we reconstructed the final days of both victims, verified witness accounts, where possible, and found evidence that suggests the men drowned because of a new tactic by the Greek coastguard of throwing small groups of asylum seekers overboard and making them swim to Turkey.

METHODS

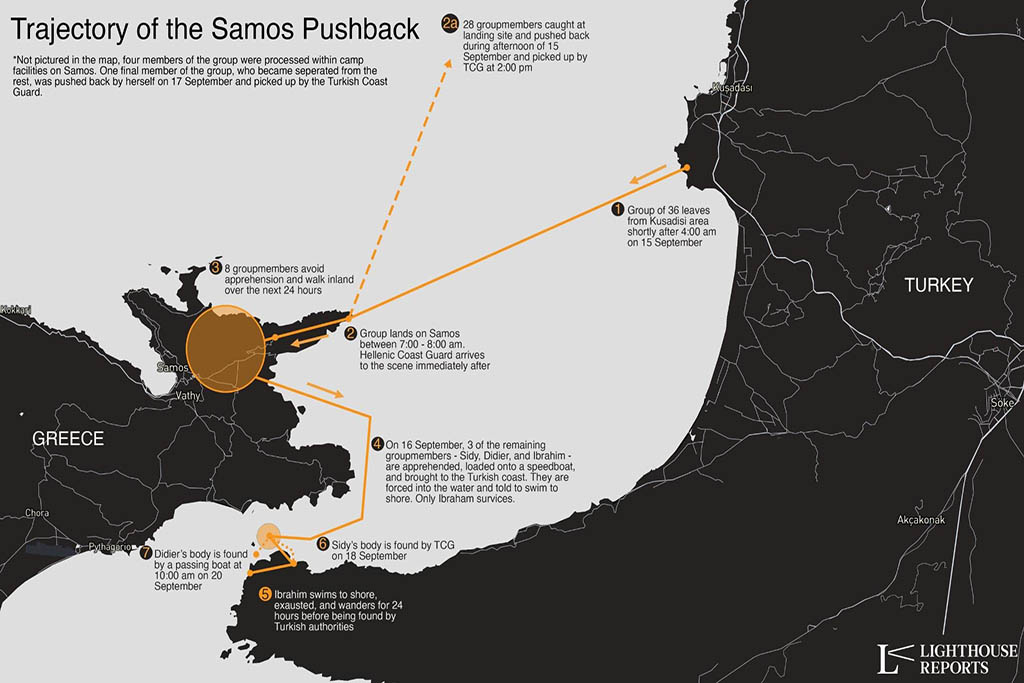

On the morning of September 15 a group of 36 people arrived on the Greek island of Samos on a small vessel after having left Turkey overnight. Shortly after arriving on Samos, the asylum seekers realised their presence had been detected. A photo taken by one of the group shows how Greek coastguard vessel had approached them. In a voice message we obtained, one of the group members described officials moving in on them by land as well.

According to seven witnesses we interviewed, Sidy, Didier and Ibrahim were among the few asylum seekers who initially managed to escape the Greek border forces that morning. A much larger group of 28 was caught while still near the beach and taken to a ship. The coastguard tow them out to sea, back towards Turkey, where they were cast adrift on two inflatable life rafts. Hours later, Turkish coast guards brought the 28 ashore — photos and videos show the group on black life rafts just before they were rescued.

Out of the eight people who evaded initial capture on Samos and hid in the forest, four made it to the reception and identification centre of the island, where they were registered. One woman was arrested and pushed back, left adrift on a small rubber boat — as shown on pictures taken by the Turkish coast guard.

Sidy, Didier and Ibrahim were captured a day later by Greek authorities. According to Ibrahim, the sole survivor of the three, they were driven to a port, put on a speedboat, beaten and thrown into the sea without a life jacket. Sidy and Didier both drowned, Ibrahim was able to swim to the coast and discovered Sidy’s body on the shore nearby. Didier’s body was later found floating in the shallows not far from the mainland by the Turkish coast guard.

Ibrahim’s testimony cannot be corroborated by other witnesses but we were able to verify important details of his account. For example, he testified that the waves were high that day, which matches the weather report that states the winds were strong. Ibrahim also said that when he saw Sidy’s body on the Turkish shore he put a stick in the rocks next to it so people could find it later. This stick is clearly visible on photographs taken by the Turkish coast guard when they came to collect the body.

Two whistleblowers, Greek officials with direct knowledge of coastguard operations, who spoke on condition of anonymity, confirmed that what Ibrahim described had happened before to asylum seekers. The rationale, the sources said, is to avoid using life rafts when possible because they are expensive and any public tender for their replacement might raise questions about their use. We found that at least 29 other alleged incidents of people being thrown overboard had been recorded by the NGOs like Aegean Boat Reports and the Turkish coast guard since May last year. A full breakdown of the open source methodology used to support this investigation can be found here.

STORYLINES

The UN estimates that close to 3,000 people were dead of missing after trying to reach Europe across the Mediterranean and the Aegean. Many of the dead and missing remain anonymous. We visited the families of Didier Martial Kouamou and Sidy Keita in Cameroon and in France, we met their travel companions in Turkey and Greece and found Sidy’s numbered and unnamed grave in Turkey to ensure their stories were told.

Sidy Keita, 36, had to leave his home country, Ivory Coast, fearing for his safety after he demonstrated against the president. Didier Martial Kouamou, 33, father of two, had worked as a mechanic in Cameroon and wanted to join his brother Séverin who works in a cell phone shop in Paris. Both Sidy and Didier wanted to apply for asylum in Europe.

Séverin blames himself for Didier’s death. His aunt Marinette, who raised Didier said “The news of his death broke us all.”

Sidy is buried in Izmir’s Doğançay Cemetery, the “cemetery of the nameless” in Turkey, for people whose relatives cannot afford a headstone. One of Keita’s acquaintances, whom he had met on his way to Europe, collected money at his funeral service in Izmir. But the money was not enough to have the body transferred to Ivory Coast. There are no flowers on the grave, Der Spiegel writes after visiting the cemetery. There is no inscription with his name or the dates of his birth and death just wooden sign with the number 68091.

To keep up to date with Lighthouse investigations sign up for our monthly newsletter

The Impact

Our investigations don’t end when we publish a story with media partners. Reaching big public audiences is an important step but these investigations have an after life which we both track and take part in. Our work can lead to swift results from court cases to resignations, it can also have a slow-burn impact from public campaigns to political debates or community actions. Where appropriate we want to be part of the conversations that investigative journalism contributes to and to make a difference on the topics we cover. Check back here in the coming months for an update on how this work is having an impact.