Frontex, the EU Pushback Agency

Frontex’s internal data shows EU border agency involved in mass pushbacks

Europe’s border agency Frontex is facing intense scrutiny over its complicity in illegal pushbacks in the Aegean after more than two years of revelations by Lighthouse Reports. The agency has consistently denied its involvement, but a joint investigation of Frontex’s internal database – together with Der Spiegel, SRF Rundschau, Republik and Le Monde – shows that Frontex is implicated on a far greater scale than previously uncovered.

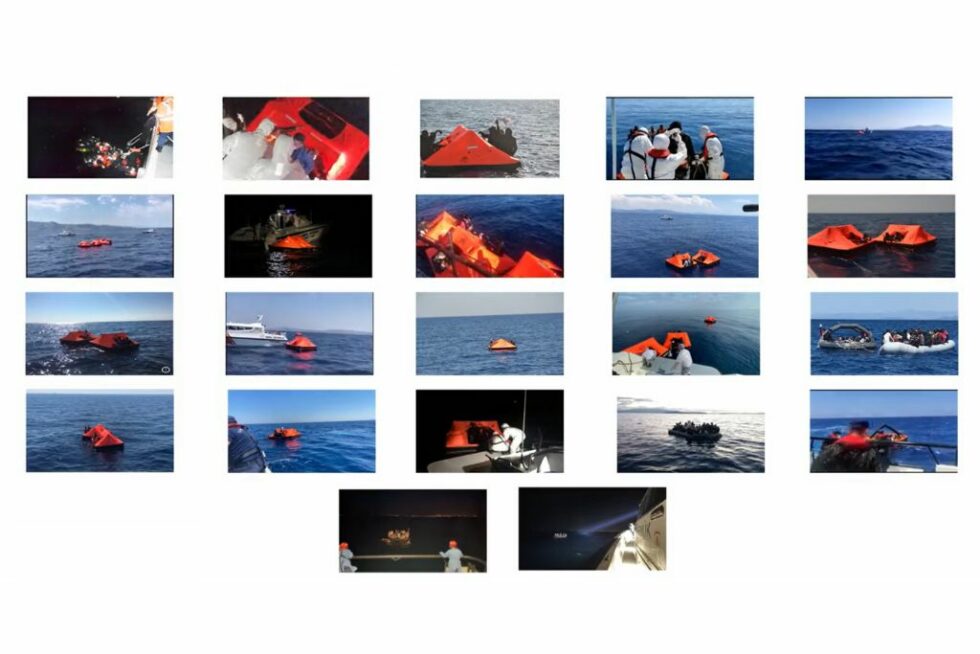

Data recorded in its internal Joint Operations Reporting Application (JORA) database, when cross-referenced with other sources, indicates that Frontex was involved in at least 22 verifiable cases where people were put on life rafts before being pushed back to Turkey over the course of 18 months between March 2020 and September 2021.

The estimated 957 people involved, according to JORA data, would therefore have been placed in dangerous and life-threatening situations after being spotted by Frontex assets in the Aegean. In two cases, people had reached Greek islands before being put on life rafts and left adrift on the open sea.

The real number of pushbacks undertaken with Frontex involvement, however, is likely to be much higher. In the same time period, Frontex recorded its own role in 222 incidents listed as “prevention of departure”, involving 8,355 people.

The term “prevention of departure” is commonly used to report practices better known as pushbacks, illegal under Greek, EU and international law. This was confirmed in interviews with several sources within Frontex as well as the Greek authorities.

METHODS

Lighthouse Reports obtained the JORA database via a Freedom of Information Request. Frontex sent a redacted version of the database and deleted all descriptions of incidents, but accidentally provided descriptions for 145 incidents which took place in the Aegean between April and August 2020.

The database, in use by Frontex since 2011, includes more than one million lines and 137 columns. Our data team analysed the information contained and was able to identify reporting patterns which point to cases of pushbacks.

The incidents have an almost identical description: a Frontex asset (plane, helicopter, vessel or drone) detects a migrant boat crossing from Turkey and warns the Greek Coast Guard. The Coast Guard informs the Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre in Greece and Turkey, after which the Turkish Coast Guard returns the boat to Turkey. The incidents are registered in JORA as “prevention of departure”, and include the estimated number of people stopped from entering the EU, and a tick-box to signal Frontex involvement.

Cross-referencing incidents in JORA with those recorded in other databases, such as the Turkish Coast Guard’s as well as the NGO Aegan Boat Report’s, plus gathering additional visual evidence, we initially confirmed Frontex was involved in 22 pushbacks concerning 957 people. They were put in life-threatening situations on the open sea, left adrift on inflatable vessels without engines until the Turkish Coast Guard picked them up.

But between March 2020 and September 2021, Frontex was involved in a total of 222 incidents which it recorded as “prevention of departure”, amounting to 8,355 people. Sources within Frontex, the Greek Coast Guard and the police all confirmed that the term “prevention of departure” is used to indicate pushbacks.

This discovery not only demonstrates the scale of Frontex’s involvement in illegal practices at the EU’s borders, but also highlights how the agency uses misleading terminology in its reporting system, which – whether intentionally or by oversight – conceals human rights violations.

STORYLINES

On 13 May 2020, Amjad Naim, from Palestine, together with almost 30 other asylum seekers, had almost reached the coast of Samos. On 28 May 2021, Aziz Berati, his wife and his two children, reached the coast of Lesvos, Greek territory.

Their cases are one year apart, but their stories are similar. Both men, and their families, were violently pushed back by the Greek Coast Guard. Hours after being intercepted, in Greek waters, or on Greek land, they found themselves on engineless life rafts, left adrift in the Aegean, until the Turkish Coast Guard picked them up.

The cases of Amjad and Aziz are but two of a much larger number of pushbacks carried out by the Greek Coast Guard, with the complicity of Frontex. As the EU border agency registers in its own JORA database, Frontex detected the boats crossing and warned the Greek Coast Guard. What happened after can be confirmed by visual evidence coming from the asylum seekers themselves, by NGOs such as Aegean Boat Report, and by the Turkish Coast Guard database.

These incidents are registered in JORA under the term “prevention of departure”, a seemingly innocuous, bureaucratic term which instead covers violent, illegal practices taking place at EU borders.

Lighthouse Reports and its media partners spoke to two Frontex officers who confirmed that the term “prevention of departure” is often used to indicate pushbacks. Greek authorities, speaking on condition of anonymity, also confirmed the practice. One Greek Coast Guard officer wondered “why don’t they just call it pushbacks and get over with it”.

Incidents reported in JORA go through several rounds of verification, and more information, or clarification, can be asked anytime before an incident is “approved” by the Frontex Situation Centre in Warsaw. However, according to sources within Frontex we spoke to, this process is more of a “rubber-stamping” exercise, than actual verification of information. All with the purpose of not damaging relations between the agency and the host member state. And conveniently hiding information in the process.

To keep up to date with Lighthouse investigations sign up for our monthly newsletter

The Impact

Our investigations don’t end when we publish a story with media partners. Reaching big public audiences is an important step but these investigations have an after life which we both track and take part in. Our work can lead to swift results from court cases to resignations, it can also have a slow-burn impact from public campaigns to political debates or community actions. Where appropriate we want to be part of the conversations that investigative journalism contributes to and to make a difference on the topics we cover. Check back here in the coming months for an update on how this work is having an impact.