Europe’s Nameless Dead

As more people try to reach Western Europe through the Balkans, taking increasingly dangerous routes to evade border police, many are dying without a trace

When hundreds of thousands of refugees crossed through the Balkans in 2015, border controls were limited and there were few fences or walls. The route was largely open.

After several years of lull, the number of people making this journey recently increased again. Last year saw the highest number of crossings since 2015, predominantly due to ongoing conflicts in Afghanistan and hostile treatment of refugees in Turkey.

But the Balkan route has changed in the last eight years. With the help of funding from both the EU and the UK, countries in the Balkans have erected fences and built walls. When border police catch people seeking asylum, they often force them back over the border.

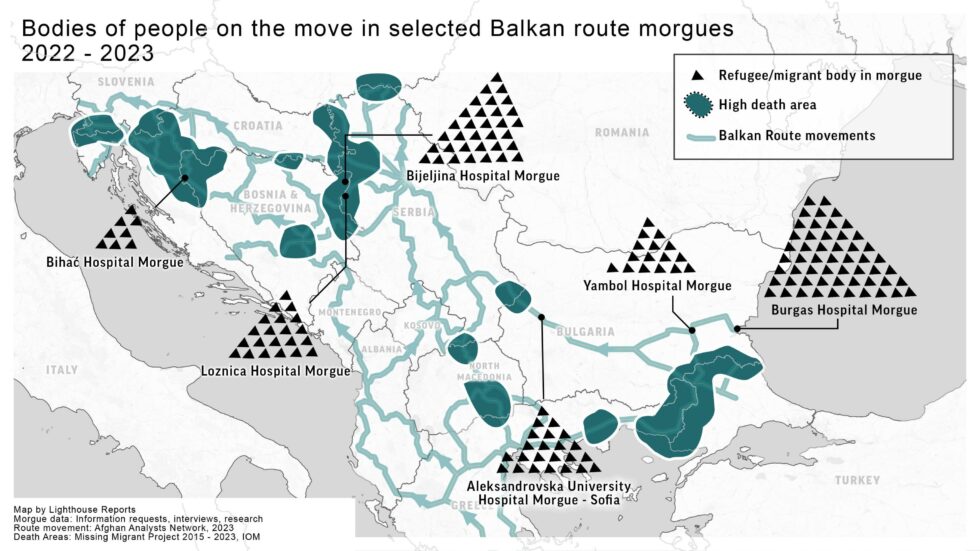

Subsequently, those making the journey often take longer and more dangerous routes in order to evade the police – and the consequences can be deadly; people are freezing to death in forests, drowning in rivers or dying from sheer exhaustion.

There is no official data on the number of dead and missing migrants in the Balkans. Efforts that have been made to collect data – for example the IOM’s Missing Migrants Project – are based mostly on media reports and are likely to be significantly underestimated.

With RFE/RL, Der Spiegel, ARD, the i newspaper, Solomon and academics from Aston, Liverpool and Nottingham Universities, we sought to measure the scale of migrant deaths at the borders of a commonly trodden route spanning Bulgaria, Serbia and Bosnia. Crucially, we sought to find out what subsequently happens to the bodies of these people and what their families go through trying to find them.

We found that the hostility people face at the borders of Europe in life continues into death. State authorities make little to no effort to identify dead migrants or inform their families, while individual doctors, NGO workers and activists do what they can to fill in the gaps. Unidentified bodies end up piled in morgues or buried without a trace.

METHODS

It was clear from the outset that it would be impossible to get comprehensive numbers on migrant deaths, given some bodies will never be found, particularly when people have drowned in rivers or died deep in forests.

In Bulgaria, Serbia and Bosnia, we requested data from police departments, prosecutors’ offices, courts and morgues on how many unidentified bodies they had recorded in recent years. While some provided information, most failed to respond or declined to disclose the data.

But through this process we managed to obtain data on the number of bodies known or presumed to be migrants received by six morgues near the borders along the Bulgaria-Serbia-Bosnia route. We found 155 such cases across the six facilities since the start of 2022 – the majority (92) dying this year alone.

By speaking with forensic pathologists in Bulgaria, Serbia and Bosnia, we found that in each of the three countries, the legal protocol is that an autopsy must be performed on all unidentified bodies – but what happens next is less clear. Information on the deceased is fragmented and held across different institutions, with no unified system which proactively seeks to connect them with families looking for them.

Through interviews with more than a dozen people whose family members had gone missing or died along the route, we learnt that they are left with no idea where to look or who to ask. We found WhatsApp groups and Facebook pages connecting networks of concerned families, desperately sharing photos and information about their lost loved ones. Some NGOs in Bulgaria and Serbia said they are contacted about such cases every day.

In some cases when families approached Burgas morgue in south-eastern Bulgaria – where we recorded the highest number of migrant bodies – they were told by staff that they could only check the bodies if they paid them cash bribes. This was confirmed by multiple testimonies and NGOs operating in the area.

STORYLINES

RFE/RL followed the case of one Syrian father’s search for his son. Husam Adin Bibars, a refugee in Denmark, travelled to Bulgaria after his son, Majd Addin Bibars, went missing there while trying to reach Western Europe.

After a day and a half of asking different institutions, Bibars was directed to a local police station near the Turkish border – where he was shown a photo of Majd’s lifeless body. He was told he had died of thirst, exhaustion and cold – and that he had been buried four days after his body was found.

In an interview with ARD, the prosecutor in Yambol, a Bulgarian city close to the Turkish border, near where Majd was buried, said his body was buried after four days in keeping with their procedure of carrying out burials of unidentified migrants “fast” to free up space in the morgue.

Some 900 kilometres away in Bosnia, iNews spoke to Dr Vidak Simić, a forensic pathologist responsible for performing autopsies on bodies found in the Drina River, which runs along the Serbian border. He said that in 2023 alone, he had examined 28 bodies presumed to be migrants, compared with five last year. The vast majority remain unidentified and are now buried in graves marked ‘NN’ – an abbreviation for a Latin term for a person with no name.

The doctor is now working with local activist Nihad Suljić to try to help families find their missing loved ones, by checking his autopsy files to see if any unidentified bodies match the description of missing people. But he says a proper system needs to be put in place for this. “[Families] enter a painstaking process, through embassies, burial organisations, to obtain a bone sample, so that they can compare it with one of their family members,” he says.