The Crotone Cover Up

Italy lied about its role in a shipwreck that killed 94 people – including 35 children – and the EU border agency Frontex helped cover it up

During the early hours of February 26, 2023 a wooden pleasure boat crashed close to the shore in Cutro, Italy. On board were nearly 200 people, mostly refugees from Afghanistan. At least 94 of them died, including 35 children. Yet the overloaded boat had been spotted by Europe’s border agency Frontex six hours before the wreck, struggling in bad weather. The deaths, which took place so close to the shore, shocked Italy and Europe. But Frontex and the Italian authorities deflected blame onto each other.

Frontex said that the boat showed “no signs of distress” and that it was up to Italy to decide whether to launch a rescue operation. Italy’s prime minister claimed that they didn’t know the boat “risked sinking” and didn’t intervene because Frontex didn’t send them an ‘emergency communication’. “Do any of you think that the Italian government could have saved the lives of 60 people, including a child of about three years whose body was just found today, and it didn’t?” Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni said shortly after the tragedy.

A joint investigation by Lighthouse Reports and its partners reveals that both the Italian authorities and the Frontex leadership were aware that the boat was showing signs of distress when the ship was first spotted six hours before the wreck, but nevertheless decided not to intervene – and later tried to conceal how much they knew.

METHODS

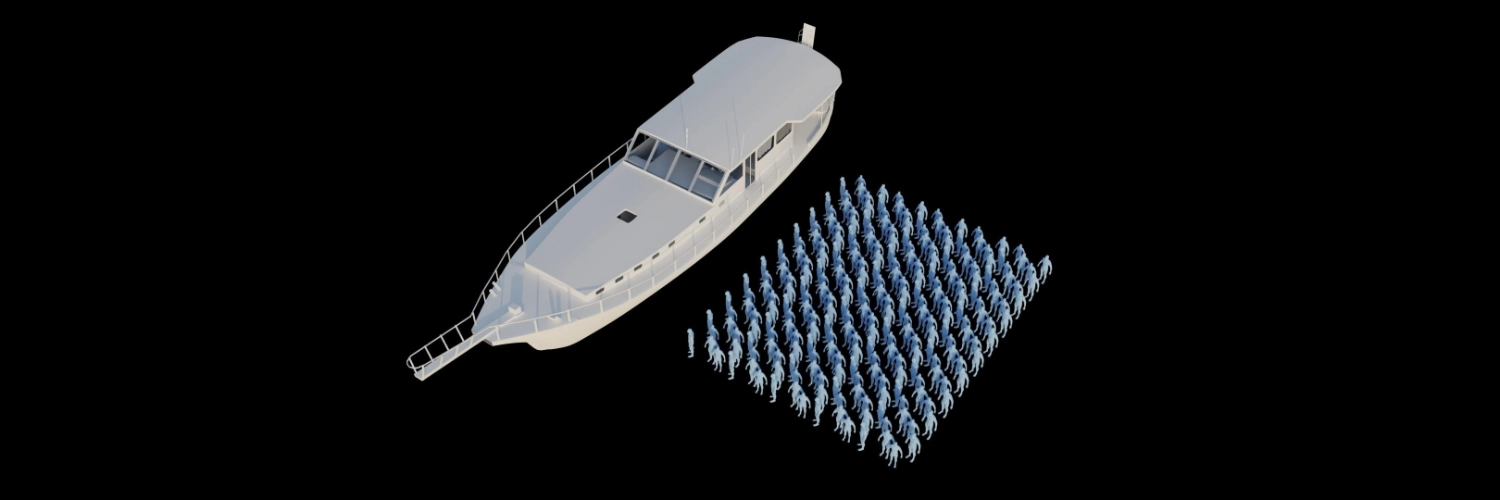

When images of boat debris on an Italian beach were broadcast around the world, it was hard to imagine that they came from a vessel carrying 200 people. The Summer Love, a wooden boat approximately 25 metres long, was crammed with women, children and men fleeing wars, hoping for a better life. With little video footage available, we decided to make a 3D model of the vessel to better understand and explain the risks people were prepared to take. Crowded below decks, they had little chance of survival when the boat sank as their only exit was one narrow staircase.

Over time, our reporters won the trust of some of the survivors by spending time with them in the centres they’re now living in. They shared their stories from departing Turkey to the harrowing losses they suffered in the sea. Some shared videos which revealed additional details about the shipwreck, including a tablet with navigation software which confirmed the vessel’s location and direction of travel.

Crucially, we obtained leaked confidential Frontex mission reports which revealed that a plane operated by the border agency had reported signs of distress to both the agency and Italian authorities. Hours before the flight, operators warned about “strong winds” in the Ionian Sea. Frontex then detected the vessel by tracking multiple satellite phone calls made throughout the day by people on board. A detailed account of the pilot’s calls show that Frontex knew it was a “possible migrant vessel,” with no visible safety jackets and a “significant thermal response” from below deck. According to Frontex’s press office, this is an indication of the presence of an “unusual” number of people on board.

Bad weather, a lack of life vests and overcrowding constitute signs of distress under Frontex’s and Italy’s own maritime rules; still the maritime authorities did not launch a search and rescue operation. After the wreck, the European border agency concealed the fact that their pilot had signalled strong winds to their control room during the surveillance flight.

STORIES

Assad Almulqi was a child when war broke out in Syria. His family fled their city after it was attacked with poisonous gas in 2013. This year, the 22 year-old paid 8,000 euros for a place on the boat from Turkey. His six-year-old brother Sultan was allowed to travel for free.

He recalls the moment everything went wrong. “It was dark. The ship leaned to one side and half of it went underwater. It sank in seconds.”

“I got scared, held my brother in my arms and told my uncle that we needed to go upstairs because something not normal was happening. The waves started hitting the windows and water entered the ship.”

He jumped out when the water reached his knees, holding his brother tightly.

Assad tried desperately to keep Sultan above the waves as he attempted to signal to rescuers. “We were drowning ourselves to keep his head above the water, but it wasn’t enough to save him.”

They clung to pieces of the ship, fighting to stay afloat as people around them drowned.

Also onboard was 23-year old Nigeena who was travelling with her husband Seyar, following their wedding just four months earlier. She clutched his hand as they fought to stay above water. They were almost ashore when a huge wave swept Seyar away. Their boat broke apart 200 metres off the coast of Italy.

“The wreck is Italy’s fault because they knew from the start that a boat had arrived,” said Nigeena. “Usually when they see an unfamiliar ship it’s their job to check it out. But they didn’t.”

Lawyers for some of the families of the victims are planning to take a case to the European Court of Human Rights, arguing Italy should be held responsible for the “irremediable violation of migrants’ right to life.”